Mercury Propellers: from wax to works of art

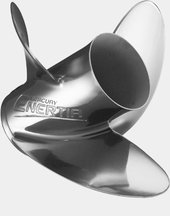

No matter how much horsepower a boat engine generates, a quality propeller will turn that power into performance, and Mercury Marine is known for producing the world’s best propellers. Housed in Plant 98 in Fond du Lac, Wis., Mercury Propellers employs craftspeople who create stainless-steel works of art.

Mercury makes its stainless props using the “investment casting” method. In the first step, a propeller is formed from a proprietary wax compound. Every detail including the part number and logo is formed in the wax tooling. The wax propeller is then dipped repeatedly in a liquefied ceramic solution to create a shell that surrounds the wax model. After the shell dries, the ceramic-coated wax propeller is placed in an oven-like device called an autoclave to melt the wax, leaving the hardened shell.

Next, the propeller molds are placed in a different oven and are pre-heated. The shells are then placed on a heat-proof platform where molten liquefied stainless steel is poured into them. Within minutes, the steel starts to cool and the shells begin to crack as the propellers harden. After the steel cools, the shells are removed and the propellers are sandblasted to a matte finish. Traditionally, stainless steel propellers were hand-finished by craftsmen who ground the props on machines to achieve the desired finish. This laborious process produced quality pieces, but limited volume.

Today, Mercury uses a process called “drag finishing” to polish its stainless steel propellers. Several props are attached to a rotating carousel-like device and are dragged through a large tub of resin and silica “stones” called “media.” The size, shape and density of the media, as well as the speed, lubricant levels and operating times of the machine determine how much steel is removed from the prop. After the last step of the finishing process, the propellers shimmer with a mirror-like finish.

Media finishing, however, hasn’t replaced the craftsmanship of the individual propeller grinder. High-performance props receive extra attention from a select group of Mercury artisans to ensure the propellers make the most of the power that turns them.

A snowball's chance

The snowmobile market was growing in the mid-1960s, and Carl Kiekhaefer decided that a small “sled” powered by a two-cycle engine would be an ideal “ice breaker” for Mercury that would provide winter sales opportunities for boat dealers up north.

Kiekhaefer felt strongly that a 15hp engine with electric start and heavy-duty transmission, chassis and cowling would sell.

The Mercury “Snow Vehicle” — the 150E — slid its way into the market in 1968, but it was slow, heavy and unstable. Oval-track-tested, the machines performed well turning left — the direction of the test track — but were known to tip on right turns. Customers and dealers complained. Rather than pay to ship defective models back, dealers were instructed to burn the sleds and send in a photo to collect the refund.

Better performing models named after classic Mercury outboards — the Rocket, Lightning and Hurricane — didn’t snowball into better sales, so the focused switched to racing. In 1973, the Mercury Sno-Twister began dominating race circuits and continued winning for more than a decade after production ceased.